If trees grow where you live, then cutting them can be a rewarding stewardship responsibility. It can also be a great way to heat your home. I’ve been cutting firewood and heating with it for 30 years, and there are five main steps to the process. Learn to do these yourself and you’ll enjoy a sustainable, affordable and effective source of off-grid heat.

Step 1: Cut down a tree

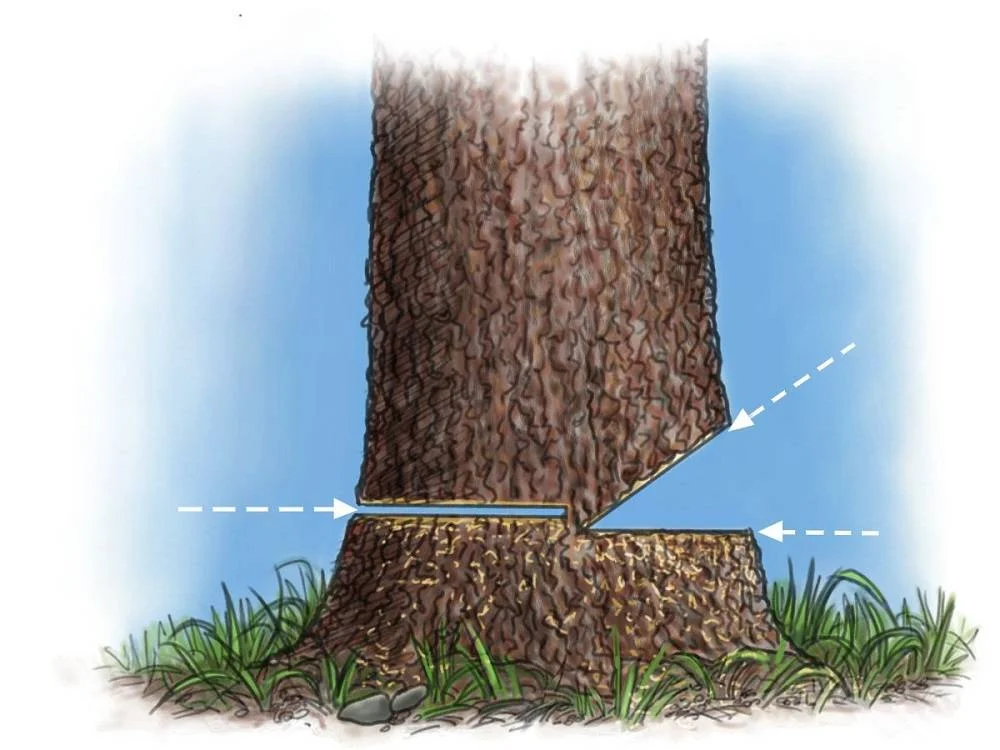

There are three cuts needed to safely fell a nearly vertical, complication-free tree. If a tree is leaning heavily in one direction, or if it’s within two trunk lengths of a power line or building, don’t cut it down yourself. The risk is too high. Hire an experienced and insured arborist if the tree needs to come down.

Before you get started, cut and remove any saplings, bushes or dead branches from around the tree. You’ll need a clear escape route to briskly step away from the tree as it falls. Now’s the time to create one.

The first two of the three felling cuts you’ll make in the trunk create a wedge of wood that’s removed from the trunk, some distance up from the ground and one-third of the way through, on the side that the tree will naturally fall toward. The third felling cut is horizontal, entering the side of the trunk that’s opposite the wedge, 5 cm (2 inches) above its bottom face, and extending inward within several inches of its point. The fact that the third cut doesn’t intersect with the first two is key. It’s this feature that preserves uncut wood fibres across the centre of the trunk, creating the all-important hinging action that keeps the tree under some control as you step aside yelling “Timber!” Put on your safety equipment, start up the saw, rev it to full speed, then move the spinning chain into the trunk to make the three felling cuts.

Step 2: Crosscut log to length

Now’s the time to use your chainsaw to cut logs into lengths that fit your wood stove or fireplace. Measure the space inside your wood-burning appliance, then subtract 2.5 cm (1 inch) to get the firewood length you need. It’s common practice to eyeball the length of firewood blocks being cut from logs, but there are two problems with this: besides the fact that a pile of firewood of varying lengths can’t be stacked neatly, it’s a pain when you can’t close your wood stove or fireplace insert door properly if you happen to cut the odd block too long. That’s why I always take the trouble to mark logs before cutting. Make a measuring stick to the firewood length that’s ideal for your setup, then use it to guide a hatchet for marking the block length. A couple of hits with the blade makes a mark on the bark that ensures consistency when sawing.

As you work, keep the cuts square. Also—and this is vitally important—avoid letting the saw chain hit soil or rocks underneath the logs as they sit on the ground. Even a split-second contact with a small amount of dirt will turn a razor-sharp chain into a near-useless assembly of spinning metal. A dull chain can be re-sharpened, but the process takes anywhere from 10 to 30 minutes. A two-part cutting process is key to avoiding trouble. Make each crosscut three-quarters of the way down through the log as it lays on the ground, then roll the log and complete the cuts from the top. I use a cant hook to help rotate large, heavy logs.

Responsible Forest Management

Being a good steward of a back-40 forest isn’t the same as dealing with commercial forestry challenges, because you’re managing for different goals than those pursued in industry. While you might be aiming for firewood and lumber production, you’ll also want to keep the forest friendly for wildlife and sustainable for future generations.

Hollow yet sound trees may not look great, but they’re valuable. Depending on where you live, you should leave three to 12 cavity trees standing per acre for wildlife habitat. Dozens of species of birds and mammals depend entirely on cavity trees for shelter, hibernation and rearing their young. Trees with openings in the upper trunk are especially valuable, since they afford the best predator protection.

When I cut trees on my land, I always follow a three-step selection process. First trees to get cut are the ones that blow down in wind. Next are gnarled, stunted or damaged standing trees. Large, mature, high-quality trees are cut last, specifically the individuals blocking the light and space needed by younger trees.

Just don’t overdo the sunlight thing. Dappled sun on the ground is OK in a forest, but a lot of full sunlight can allow the growth of grasses that would prevent new trees from starting.

Step 3: Split your firewood

There are two reasons firewood needs to be split along its length. Besides making the firewood smaller and easier to handle, splitting allows wood to dry more quickly and thoroughly. A gas-powered wood splitter is easier to use than an axe for knotty wood or blocks longer than 46 cm (18 inches), but a good splitting axe is faster for straight-grained logs, especially oak, ash and aspen. Bolting two old car tires together makes a great log holder, keeping the wood upright while splitting.

Too many people struggle unnecessarily at this stage because the axe they use for splitting is far too light and far too thin. A 2.75 kg (6 pound) or, better yet, a 3.5 kg (8 pound) splitting axe is a far more effective choice. Just don’t be fooled by the weight. The extra inertia is enormously more effective at splitting wood apart than what’s generated by a lighter axe.

Step 4: Stack your firewood

After 20 years of stacking wood in the usual straight piles, l switched to something better. I lay out round wood piles with a 1.5-metre (5 foot) length of rope that has a loop in one end. Push a 0.3-metre (12 inch) long metal spike into the ground where the centre of the pile will be, then pull the rope tight and use the end to guide placement of the outside ends of the logs making up the bottom layer of wood. Keep stacking and checking several layers around the perimeter of the circle, using the end of the rope as a guide, then remove the stake and rope and continue stacking by eye. Fill the centre of the circle with randomly thrown-in pieces of wood after you’re a few feet up, then build more wall when you’ve filled the centre portion, tilting the wall inward slightly for stability as you go up. Add a couple of 3-metre (10 foot) long wooden poles across the diameter of the circle when you’re about 1 metre (4 feet) up, to bind the sides of the pile together, then dome the top and place a tarp under the last layer of wood for shelter. Another layer or two of wood on top holds the tarp down and keeps the pile dry.

Step 5: Season your firewood

The fresher the better for vegetables and fish, but not so for firewood. My rule is to allow at least one year of drying before burning firewood. Two years is better. The tarp I install as part of my round wood piles is especially effective because it’s protecting a wider width of stacked wood than in a conventional narrow, straight pile. This tarp is also sloped. Storing firewood in a well-ventilated, covered woodshed is the very best option because it yields noticeably hotter and cleaner-burning fires. That’s the reason old-time homesteaders usually had a woodshed near the house.

Cutting your own firewood is like an exercise program that also keeps you warm and saves money. Learn the basics and you’ll be healthier and wealthier.

Steve Maxwell and his wife Mary live on a 90-acre modern homestead on Manitoulin Island, Ontario in a stone house they built with local materials beginning in 1985. Steve is Canada’s longest-running home improvement and how-to columnist and editor of Home and Property. He divides his time working on the land, building things large and small, and creating articles and how-to videos that teach sustainable, self-reliant, hands-on living skills.