In Minimalism: A Documentary About the Important Things, producers Matt D’Avella, Ryan Nicodemus and Joshua Fields Millburn go on the road, speaking to people about their way of life and showcasing a more stripped-down, less-consumerist lifestyle. From tiny-home adopters to corporate ladder dropouts, the film’s subjects reveal that stuff doesn’t make us happy—a life with purpose and meaning does. As it turns out, a happy life also happens to be a more sustainable life.

SustainableJoes founder Stephen Szucs would agree. In fact, he would argue that a sustainable life is the only life.

Although Szucs now lives in Toronto, it’s not surprising to learn that the environmental activist grew up on a family farm in Simcoe, Ontario. “SustainableJoes started purely as a passion project,” says Szucs. “My sister got sick, and it was one of those life-is-really-fragile moments. Thankfully, Amanda is OK, but it made me think, ‘What do you want your life to stand for?’ For me, sustainability is the only thing worth living for. If our existence is not sustainable, we are not going to sustain ourselves into the future.”

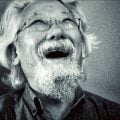

For his Rethink tour, SustainableJoes founder Stephen Szucs went

on the road, campaigning for sustainability and sharing tips for a

greener lifestyle.

So Szucs launched SustainableJoes, which aims to make sustainability easy for “Everyday Joes & Jaynes.” To start, Szucs embarked on a sustainability experiment. “Year 1 was living off-grid in an urban centre, creating less than one bag of garbage for the whole year,” he says.

His experiment picked up traction and led to Year 2, which involved the Rethink tour, where Szucs rode a solar- and pedal-powered trike for six months, delivering his message of stewardship and sustainability. “It was wild. I stayed everywhere from people’s backyards to extravagant houses,” he says. “But the idea behind the tour was to get people to rethink their practices when it comes to sustainability.”

That tour led Szucs to make a film (SustainableJoes—The Time Is Now). “It was originally intended to illustrate that people everywhere believe something has to change,” he says. “However, it turned into a crash course on sustainability, empowering ‘Everyday Joes & Jaynes’ with tools to take positive action.”

By choosing a more sustainable lifestyle, Szucs says, we can help care for the world that sustains us. “Whether we’re talking about your dishwasher or a nice glass of wine, we need to look at how it impacts the world,” he explains, pointing out that a standard glass of wine takes 90 litres (190 pints) of water to produce. “It’s crazy, but we’re all going to keep drinking wine. People have been drinking it for thousands of years. So how can we make our practice more sustainable?”

As it turns out, living a sustainable life also means stripping away the noise, stuff and distractions that get in the way of a more meaningful life.

“Less is more, absolutely,” says Kay LeFevre, a professional rug hooker who left a life of domestic bliss for life on the road. In 2014, LeFevre sold her Windsor, Ontario, home and got rid of most of her belongings to move into an RV for greater freedom and mobility. “You can’t find happiness with a mega-mansion and art hanging on the walls,” she explains. “It’s all about meeting people, travelling to different places, and new experiences. There’s a lot to be said for being on the move: you minimalize, and value relationships more than that new steel fridge. It cuts to the chase of what’s important.”

“Less is more,” says Kay LeFevre, who sold her Windsor, Ontario, home for life on the road.

LeFevre and her husband, a retired military officer who now works remotely as a manager at a computer company, gave up everything three years ago, when her mom became ill. “We lived on the waterfront, outside of Windsor. We had a beautiful life there,” she says. “Then, everything changed when Mom got sick. I had to live in her driveway while sorting out help for her. During that time, our home flooded—something that wouldn’t have happened if we’d been there. Insurance had to replace everything, so we thought, ‘Now’s the time to sell, with everything being new and finished.’ If I didn’t have that crisis, I would have probably hung on, but because it all happened so fast, I didn’t have time to get emotional. Now I don’t regret it. Things only have meaning in your memories. They don’t have meaning; you just imagine they do.”

Although LeFevre admits they chose the RV lifestyle out of necessity, it has made it easier to visit family in Canada and the U.S. “It’s amazing,” she says. “Our front windows look [out] to a new scene every day. We don’t have utility bills; we don’t have a mortgage.”

While the lifestyle suits them fine now, downsizing proved a chore at the time. “We’re both from divorces, so we had two households combined, and we had to get rid of all of that—I mean everything, even my grandmother’s china and my husband’s military medals,” says LeFevre. “They’re of no use to you. Take a picture and move on. Our kids don’t even want this stuff. It was painful, but now we don’t miss it.”

Reflecting on her RV lifestyle, LeFevre says, “Boy, have we changed. We have we changed,” she says. “We go into a store to shop, and it’s just for food or something usable. We can’t even buy clothes, because there’s nowhere to put them. You’re only thinking about how you can get rid of things, like how can I get down to one pair of jeans?”

On the road, LeFevre says she meets all kinds of people living off the grid, in vans and RVs, including seniors who don’t like the options for retirement, and millennials, and people who have been squeezed out of homeownership due to the rising prices. “Once they’ve given up everything material-wise, they realize they’re keeping the earth clean and reusing. It feels good. It’s cheaper, too,” she says.

“In our culture, there’s definitely a transition happening away from materialistic and hedonistic values, toward values that are more about meaning, spirituality, and knowledge and curiosity,” says Emily Esfahani Smith, author of The Power of Meaning: Crafting a Life That Matters, which explores what science, philosophy and societies around the globe can teach us about the search for a more satisfying and meaningful life. “You see it happening at different levels of society,” she says. “Businesses are starting to reorient toward meaning and purpose. Schools are starting to teach children about these concepts. Hospitals are starting to give patients therapy in meaning, helping them with existential anxiety. You can see it as a movement gaining speed in all these different areas.”

Born in Zurich and raised in Montreal, Esfahani Smith says that her book “grew out of a sense of dissatisfaction with our culture’s messages about what a good life is.” As she explains, “We’re constantly getting the message that if we pursue happiness we’ll get all these benefits. I realized it didn’t ring true. There were so many people I knew who weren’t devoted to the pursuit of happiness—they were concerned about having a meaningful life, helping other people or improving the world in some way. I thought that their story wasn’t being told.”

She points to research that shows the relationship between happiness and a meaningful life. “The single-minded pursuit of happiness and valuing it the way our culture encourages us to do can make us unhappy and lonely,” she says. “But pursuing meaning can bring a better sense of well-being. The book makes the argument that a good life is a meaningful life.”

Esfahani Smith also agrees that a minimalist lifestyle can help people focus on what’s meaningful to them, finding happiness along the way. “There are so many distractions today that can take us away from a meaningful life—social media, consumerism. When people simplify their lives, they’re more able to lead a meaningful life,” she says.

By focusing on a meaningful life, rather buying our way to happiness, we end up wasting less and living a more sustainable life. And if the result helps the earth, too? Nothing could make us happier.

An editor with 15-plus years in the publishing business, Catalina Margulis’ byline spans travel, food, decor, parenting, fashion, beauty, health and business. When she’s not chasing after her three young children, she can be found painting her home, taming her garden and baking muffins.