Reiner Hoyer is an award-winning Toronto contractor with 30-plus years of experience, and his favourite project is the one he built for himself and his wife, Melanie. Hoyer’s house brings together enough leading-edge construction technology that the structure requires no outside supplemental heat. Even when temperatures drop to –10ºC outdoors, the thermometer still reads a cozy 23ºC inside, thanks to nothing more than the incidental heat given off by high-efficiency lighting, small rooftop solar collectors, cooking and body heat. No furnace, no baseboard heaters, no gas fireplace necessary. Hoyer’s house is gorgeous, too. There’s no glass greenhouse look here. The indoor air quality is fresh and healthy, and anyone can build a house like this for 5 to 10 percent more than the cost of an ordinary custom home. All in all, it’s more than a good news story. Hoyer’s project proves how ultra-high-efficiency housing is possible in the real world using real trades and materials that anyone can get.

Hoyer’s project began with an energy-guzzling 1950s Toronto bungalow. The basement and one exterior wall were saved to meet zoning requirements to allow a rental suite in the basement. The result is an elegant, three-storey home built following design parameters of the Passive House movement (passivehouse.ca). Not to be confused with “passive solar” houses, Passive Houses use efficient building shape, solar exposure, super-insulation, advanced windows, leading-edge ventilation, and subtle technical features that require little or no energy inputs from conventional heating or cooling systems.

There are 25,000 Passive Houses in Europe right now, but the idea is new enough in Canada that Hoyer’s project was almost strangled by building department red tape before it ever got going. The inability of the building inspection department to efficiently recognize new-to-them construction technologies that are proven and used elsewhere was a bigger challenge than building a house that stays warm in Canadian winters without a furnace.

Super-Insulated, Super-Sealed

Retaining energy investments in heated and cooled air indoors is job No. 1 with any Passive House, and “built to code” alone will never make this happen. That’s why Hoyer built exterior walls with roughly double the usual amount of insulation: R60 for south, east and west walls, R70 for north-facing walls, and R90 in the attic. But R value alone isn’t the only issue when it comes to insulation. In fact, R values are not even the most important feature.

Most of the insulation Hoyer used is some kind of foam—either spray or rigid sheets—and there’s a reason for that. Unaffected by drafts and air movement, foam delivers consistent energy performance. By contrast, fibre-based batts are a different matter entirely. They may say R20 on the bag, but that number comes from measurements taken under ideal lab conditions in a sealed hot box. Real-world batt insulation performance is often drastically lower as air movement and drafts travel through wall frames. You can put all the building wrap and vapour barrier you want on a stud-frame wall, and air is still going to move through the insulation. You simply cannot build a Passive House without foam at least in some places.

Perhaps the most unusual part of Hoyer’s house is the approach he took to insulating the basement. He used a full-coverage design that put sheets of extruded polystyrene foam on walls, sealed under a layer of soya-based spray foam insulation. Spray foam was also used continuously over the entire surface of the existing concrete floor of the old bungalow, with floor insulation values topping out at R60. Four inches of reinforced concrete was poured on top of this floor foam, encasing radiant in-floor heating pipes. Metal stud walls sit on top of this concrete floor, located just inside the foam sprayed on the exterior walls. The result is complete thermal isolation from the earth, with a basement floor that acts as a massive thermal flywheel.

The outside three walls of the house are finished in synthetic stucco, and it’s applied over a whopping 6 inches of expanded polystyrene foam that’s anchored to a wall retained from the old house. Ray-Core structural insulated panels (SIPs) were used to create new exterior walls elsewhere. The front of the house is finished with a stone veneer that’s applied over a 2-inch-thick layer of spray foam applied over the SIPs.

The attic is filled with 30 inches of blown-in cellulose insulation, amounting to a whopping R90 of heat retention. A laser level was used during installation to ensure an even and complete attic insulation coverage.

Besides superior insulation performance, Hoyer’s heavy use of foam offers another big payoff: Spray foam seals out drafts like nothing else can, and low air infiltration is key to meeting Passive House standards. Nothing more than 0.5 air changes per hour (ACPH) is considered acceptable, and Hoyer’s house came in at an impressive 0.27 ACPH, despite the retention of that existing wall and basement from the old bungalow. That’s 11 times less air leakage than some of the highest new Canadian building code standards coming into effect right now.

Hoyer chose triple-pane Geneo windows delivering R9.5 centre-of-pane insulation values. The frames are made from a proprietary blend of fibreglass and PVC that’s strong enough to function without the need for metal reinforcement. It’s the same material used to make the bumpers of German cars, and even dark colours don’t expand and warp with the sun’s heat like vinyl can.

Evacuated Tube Solar Collectors

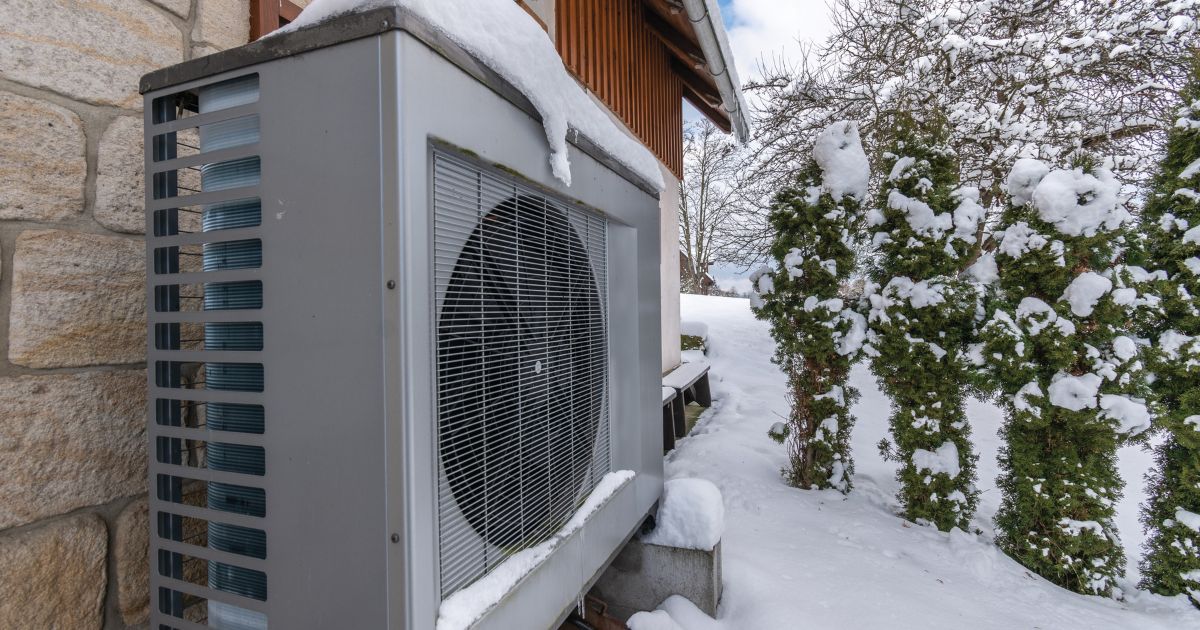

Building code requirements forced Hoyer to install an air-to-air heat pump as a backup heat source, but it’s mostly to satisfy the bean counters. The small amount of energy required for space heating beyond what’s produced internally by cooking, lighting and human bodies is usually supplied by a rooftop-evacuated tube solar collector. It provides domestic hot water too. The evacuated tube design greatly boosts heat-gathering action during cold weather. One sunny day when it was –10ºC outdoors, for instance, the vacuum tube system heated Hoyer’s 500-litre insulated water storage tank all the way up to 60ºC. Space heating is delivered through a Rehau hydronic in-floor system that also extends out onto the concrete front porch for melting ice and snow.

Fresh Indoor Air

Hoyer installed a heat-recovery ventilator (HRV) made by the European manufacturer Paul. The Novus 300 unit he chose extracts 99 percent of outgoing heat in stale air, compared with 70 to 80 percent for typical HRVs. Part of this amazing performance comes from the ground loop intake air supply. Air drawn into the HRV first travels through 90 feet of 8-inch-diameter buried pipe. Even when it’s –15ºC outside, incoming air is a much friendlier 5ºC to 6ºC as it enters the HRV. In a sense, it’s like a mini ground source heat pump without any extra equipment. A humidity recovery coil in the HRV captures and recycles moisture from the outgoing airstream, eliminating the need for a humidifier. Hoyer is currently working on plans to install a Geyser hot water heat pump to capture the heat lost by the HRV for supplemental heating on cloudy days. This heat pump will leverage the heat lost by the HRV, delivering an efficiency of about 300 percent.

At first glance, Hoyer’s project is impressive for practical reasons. Any Canadian house that stays warm without a big source of heat deserves front-page coverage. But more important than that, Hoyer has advanced the definition of what’s practical and possible in the real world. Why would anyone settle for anything less?

Old Dog Snarls at New Tricks

Anyone who thinks that building departments are useless needs to travel to a part of the world where individuals are allowed to build entirely as they see fit. Without independent oversight, the building world turns into a disaster. That said, serious bottlenecks are appearing here in Canada because building code evaluation systems don’t always have the capacity to efficiently assess and approve the flood of innovative and worthy building products. Many current code approval systems were designed at a time in history when building innovations were few and far between and slow in coming. In the minds of many building inspectors, these old processes remain. “The biggest stumbling block I faced was getting efficient approvals from city hall for a building permit,” says Hoyer. “This was a major fight that almost killed the project.”

<<<<<<<<<<<<<<

The building work itself posed challenges beyond the usual ones.

“On the construction site, I had to constantly coach every trade carefully at each step of the way, since so much of this house involved unique and crucial processes,” explains Hoyer. “No one could understand, for instance, why basement insulation was going up on walls and floors before framing, wiring and pipes went in. In the end, when workers saw how the approach created a perfect shell of insulation and air tightness, they understood. You’ve got to choose your tradespeople carefully. Their willingness to learn and work differently—without killing your budget—is key. From my experience, younger trades are more open minded and easier to teach than the guy who’s been God’s gift to the construction industry for the last 35 years.”

Does Hoyer consider all the trouble worth it?

“Absolutely,” he says. “Living in a house that costs me less than $20 a month to heat in the middle of a Canadian winter is a great thing. My wife’s breathing problems are a thing of the past now, too. Anyone can build this way at a budget very close to any ordinary custom home.”

Steve Maxwell and his wife Mary live on a 90-acre modern homestead on Manitoulin Island, Ontario in a stone house they built with local materials beginning in 1985. Steve is Canada’s longest-running home improvement and how-to columnist and editor of Home and Property. He divides his time working on the land, building things large and small, and creating articles and how-to videos that teach sustainable, self-reliant, hands-on living skills.