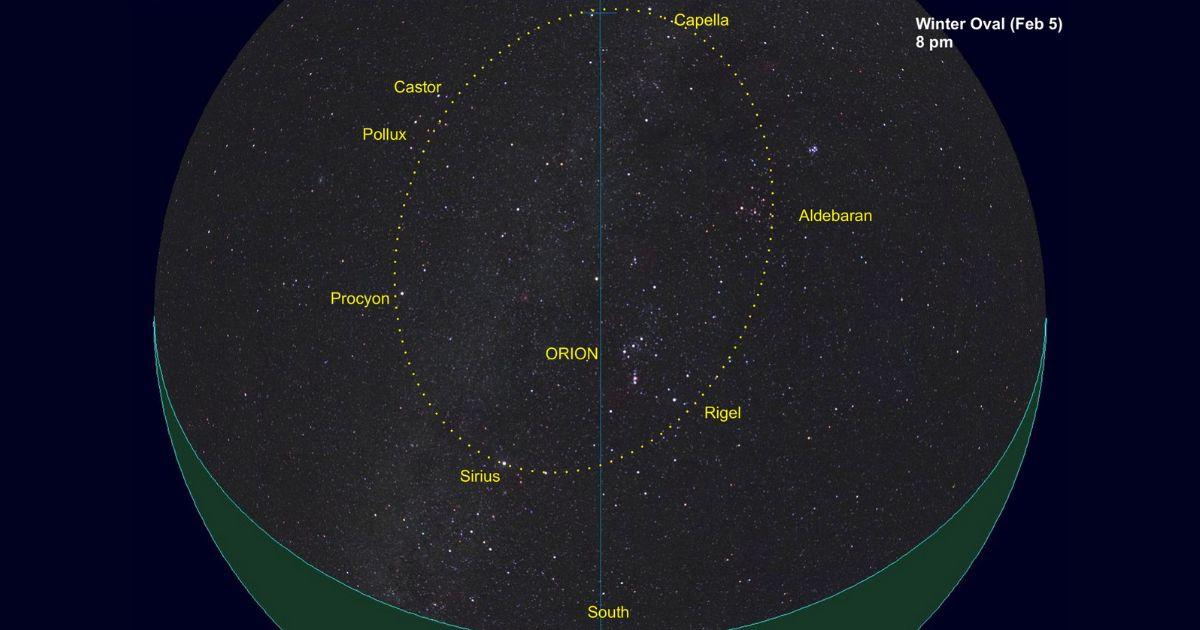

People associate areas of the night sky to particular seasons. Some areas have catchy names, like Summer Triangle and Winter Oval (seven bright stars from six different constellations). The ancients also associated certain patterns of stars with the seasons and seasonal activities (migration or agriculture). However, we need to be careful if we want to apply these celestial signs in a more precise modern context.

We are so used to our wristwatches, and now our smartphones, that we may not be conscious of how dependent we have become — not only on time, but also on time that is accurate … so everyone attends a meeting on time or catches the top-of-the-hour news. Ancients did not need time to be more accurate than what was displayed by a simple glance at the sun. Since precise time was not possible, their societies did not develop a need for it.

We don’t find the most prominent seasonal constellations on the meridian during the early evening at the four principal seasonal dates of the year: the spring equinox (March 21), summer solstice (June 21), autumnal equinox (September 21) and winter solstice (December 21). The times are shown in the four figures . The constellations are on the meridian long after sunset.

Fig. 1 Leo

Fig. 2 Summer Triangle

Fig. 3 Pegasus

Fig. 4 Orion

Since the appearance of these asterisms on the meridian occurs so late at night, they are not meant for a post-dinner stroll; instead, they’re ideal viewing for a late-nightcap walk. So although we group these stars by season, these associations are very helpful for most people. However, the “mid-season” time is not too bad. The following table gives the hours after sunset when they are on the meridian.

Several thousand years ago, when the sun was within the constellation Virgo, it heralded the time to harvest. Of course, they couldn’t see the constellations with the sun up, because they were lost behind its glare. So, ancient astronomers had to extrapolate from a month or so earlier, before the sun was in the way. Knowing the daily pace of the sun around the sky, they could predict when the sun would be at a given place. This is a simple task if you observe the sky enough to be familiar with the annual drift of the stars or sun around the sky, and this highlights their dedication to their craft.

Back in the day when these alignments were observed, say 5,000 years ago, this harvest-time alignment would occur roughly in August. But in our era, this occurs much later — at the beginning of October.

There are two main reasons for this shift from 5 millennia ago. The first reason is physical: Precession — the 25,772-year wobble of Earth’s rotational axis — causes the constellations to appear to slip in the westward direction along the ecliptic. So, the sun used to pass Spica, the brightest star in the constellation Virgo, earlier in the year than it does now. The second reason is cultural: The adoption of the Gregorian calendar in 1582 changed the calendar date of when the sun is near the star Spica by 10 days, from October 1 to October 11. Also, the number of days in the year is only an approximation, requiring regular corrections. The result //of these changes// has since undermined the ancient celestial dating strategies.

The ancients could estimate the passage of time at night by how far a celestial object moved across the sky. But this, too, has limitations. Earlier civilizations were clustered in a narrow range of latitude close to the equator. Seasonal change didn’t necessarily bring snow, but it did result in changing weather patterns, such as floods and droughts, which impacted their economies.

At these low latitudes, the diurnal path of the sun can provide a good indication for the passage of time during the day. When viewed near the equator, the sun takes close to 12 hours to cross the sky from the eastern horizon to the western horizon across this low-latitude range. But at higher latitudes, the sun’s path across the sky is more complicated, and following the seasons becomes more important because it increases the range in temperature.

At mid-latitudes (Ottawa is at +45-degrees latitude), the sun takes 15.6 hours to cross the sky in summer, but in winter it only takes 8.8 hours, since it arcs low above the southern horizon. This difference between summer and winter actually increases with latitude. Major Canadian cities range in latitude from Windsor (42.3°N) to Edmonton (53.5°N) to Iqaluit (63.7°N). At higher latitudes, the changing length of daylight gets more extreme, as the sun arcs higher in the sky in summer and lower in winter, that is until you cross the Arctic Circle and experience the midnight sun in summer and the dark days in winter.

Of course, all of this requires that we can see the stars, which may be a challenge if you live in cities covered by light pollution. Night observations need skies dark enough for us to see at least the brighter stars. This may not be possible around your home, and you may have to plan your stargazing in neighbourhood parks or perhaps a weekend camping trip in the country.

If wilderness camping is a bit too rustic for you, there are national and provincial parks with more comfortable accommodations. And some of their staff are working hard to make the experience more memorable by becoming Dark Sky Preserves. For example, Spruce Woods Provincial Park, about 200 km southwest of Winnipeg, on the Assiniboine River, became a Canadian Dark Sky Preserve in 2020. To protect the night environment and to improve the visitor experience, dozens of outdoor lights in the park have been replaced with ones that have a low ecological impact, which preserves the nocturnal ecology while still helping with late-night navigation. We hope that other park managers follow suit.

One of Canada’s foremost writers and educators on astronomical topics, the Almanac has benefited from Robert’s expertise since its inception. Robert is passionate about reducing light pollution and promoting science literacy. He has been an astronomy instructor for our astronauts and he ensures that our section on sunrise and sunset, stargazing, and celestial events is so detailed and extensive it is almost like its own almanac.