For many people, travelling with their kids on drives across the country, never mind ships or planes across the globe, is challenging. For Canadian travel writer Bruce Kirkby, however, there was no doubt in his mind when it came to setting off on a brave adventure to the other side of the world with his wife and young children.

The idea came to Kirkby during a moment of self-reflection. A wilderness writer and adventure photographer who has contributed to the Globe and Mail and won numerous National Magazine Awards, in addition to writing two bestselling books, Kirkby was scrolling between emails and social media on his phone when he

caught himself and wondered if this really was the life he wanted to continue living.

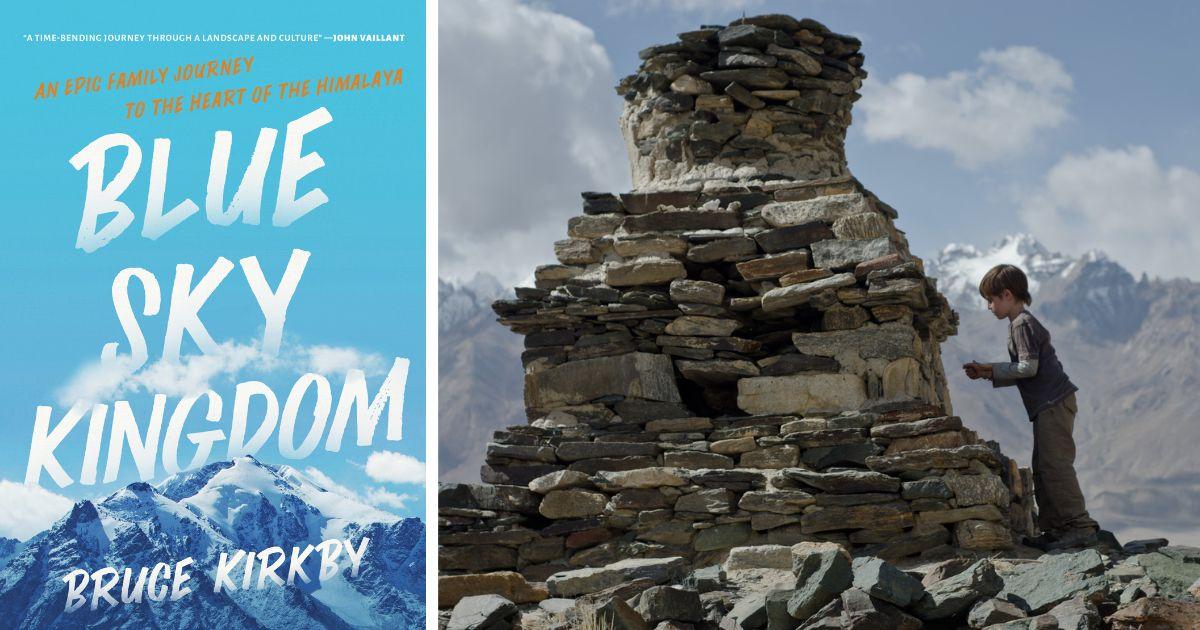

Evaluating his behaviours led to a trip with his family to the Himalayas, as well as a reality TV show following their journey. Six years later, this amazing 3-month trip, which was documented on the show Big Crazy Family Adventure, is now the subject of a book written by Kirkby himself, Blue Sky Kingdom (Douglas & McIntyre), which captures every beautiful detail of his family’s experience.

In Blue Sky Kingdom, Kirkby takes the reader along as he and his wife, Christine, their 7-year-old son, Bodi, and 3-year-old son, Taj, travel from their home in Kimberley, British Columbia, to the Himalayas without setting foot on an airplane. Using only canoe, freighter, rail and foot, the family makes their way as Kirkby searches for a deeper sense of family, community and connection.

As Kirkby will admit, it wasn’t just a physical journey, but also an emotional and spiritual one. Here’s what he had to say about travelling with his kids, his big, crazy family adventure, and his new book.

Harrowsmith: Where in the world are you right now, Bruce?

Bruce Kirkby: Right now, we’re at the lake, in southwestern B.C., about a 4-hour drive from Kimberley. We have a tradition of taking the kids out of school and coming to the cottage here, but we didn’t have to do that this year!

Harrowsmith: Where did you grow up?

Bruce Kirkby: I grew up in Etobicoke, just outside Toronto. My parents actually had a farm near Wrights Lake, east of the city. We would drive to basically Port Hope, then go north on Highway 45 towards a little town called Hastings. It was about 250 acres. We spent a lot of time in it. The funny thing was it was an inheritance from my grandmother, and she had said to my parents she’d come into some money and that she’d either get a cottage or a farm. And I mean, I love water. I love water. I’m like, why did we not get a cottage? But the farm was nice. We went there a few years ago, and it was pretty neat to be back.

Harrowsmith: How did you end up in B.C.?

Bruce Kirkby: My father dragged our family on a camping trip to B.C. when I was just 13. I still remember my first glimpse of snow-capped peaks and sapphire glaciers. From that day on, the raw wildness of that frontier called me. After graduating from engineering school at Queen’s University, I packed my rusty pickup with skis and bikes and took the Trans-Canada all the way to the windswept beaches of Tofino. I bounced around the province for years, chasing rivers and peaks and surf and snow. Eventually, Christine and I landed in Kimberley, tucked amid the quiet mountains of the East Kootenays, which has now been our home for 18 years.

Harrowsmith: Is your wife, Christine, an avid traveller, too? Have you both travelled a lot together?

Bruce Kirkby: She definitely is. I mean, our first big trip was a 24-day sea kayak. So, I threw her right in there. We hiked across Iceland together. We kayaked in Greenland. We went down the coast of Borneo. We got tossed in jail in Burma. So we’ve definitely done a bunch of stuff together. And she’s a trusted expedition partner now, really.

Harrowsmith: What was your last trip before COVID-19?

Bruce Kirkby: Our last adventure was sea kayaking on the outer coast of Vancouver Island. We took the kids out to Brooks Peninsula, which is a pretty remote part of the West Coast. And we made a 30-day paddle trip with them out there. The other thing we’ve been doing a lot recently is canoeing the Churchill River. It’s usually about a 3-week trip to northern Saskatchewan, and the kids love it. They just keep wanting to go back. So, we’ve been doing stuff closer to home. I’ve always wanted to spend a year surfing and write about it. Surfing’s kind of the yin and the yang of Buddhism and being in the moment, but a more physical “being in the moment,” and I’ve

always loved surf culture.

Harrowsmith: Your kids were seven and three at the time of your Big, Crazy Family Adventure. Do they remember it?

Bruce Kirkby: Taj is about to turn 11, and Bodi just turned 14. The trip took place in 2014. We’ve never really watched the show since, but we brought the nine discs with us, and there are nine 1-hour episodes. We’ve been watching them one a day since we got here. The kids sometimes cringe a little bit about how they were, but my goodness they are so cute. We would take Bodi on tons of trips as a baby, and people would ask why bother doing that when he won’t remember.

I wrote a column for the Globe doing research about it. Say you took a child to Africa at the age of two, or the same child graduated university and went at the age of 20 — which would have a larger impact on their life? What we know about education, early intervention, early love and early attention for our children is that they need all those formative years to form memories. With travelling, it’s more than that. I remember when we went to Patagonia with Bodi when he was 8 months old. It was really my first glimpse of what a powerful experience it was travelling with children.

In South American culture, both the children and the elders are worshipped and venerated and valued in a way that perhaps we don’t always do in North America. I remember landing in Buenos Aires and construction workers wanting to hold my baby, or being in a restaurant and the staff taking the baby to the kitchen so we could enjoy our meal. The point is that after 3 months of experiencing this culture, Bodi, even at only 8 months old, felt valued and would seek out other people’s attention, with the confidence that they would respond with love. So, in terms of the value of travelling with children, there are so many nuances to it. And I really think even that idea of a child feeling valued beyond the family in the larger community is pretty powerful, too.

Harrowsmith: Tell us about your new book.

Bruce Kirkby: Really what the book is about is our arrival in this ancient Tibet culture that’s beyond the reach of roads, in the centre of the Himalaya. We lived there for 3 months, but it seemed like we were there forever. We became part of this monastery and ancient village life. That was wonderful for the boys because they got to know all the monks. It was a very, very peaceful place. There are no phones, no power, no running water. That was a pretty special time.

Harrowsmith: What was the community like there in comparison to here at home?

Bruce Kirkby: There’s no idea of real estate because it’s the old Tibetan way of it being passed down through the family as guardians of the land. What this made me think of when you’re asking about Canada, or maybe the western world at large, is everyone obviously seeks better education, better health care, all the things we want for families and children, but what we were seeking and what I think we found there was something very special in that community. It comes with a sense of freedom.

What encapsulated it for me was a social structure called the paspun, which was unique to Ladakh (the area of the Himalaya we were living in). Every family in a village is a member of this small social structure that includes a few families. They help each other during harvest, during planting, at times of birth and death.

Everyone is a member — the kids, the elders. So, we went and helped harvest in a local village and there was a woman in her 70s who was out in the field, participating, helping, working with everyone, working with the village head, along with the kids. There was such a beauty in that, that the elders and youth belonged. After a long day, there was always time for a meal, always time for everyone to get to know each other.

They are each other’s support when they need more than just the family. I’ve made an effort to bring that into my life and the way I operate with my kids, but I wanted to share that with my book, too.

An editor with 15-plus years in the publishing business, Catalina Margulis’ byline spans travel, food, decor, parenting, fashion, beauty, health and business. When she’s not chasing after her three young children, she can be found painting her home, taming her garden and baking muffins.