Long scorned and feared, bats are synonymous with Halloween decor, cottage nightmares and Hitchcock movies. Many bat myths can easily be debunked. The expression “blind as a bat,” for example, falls flat: bats use echolocation (the process of locating objects by using sound waves and echoes) to navigate, allowing them to easily avoid obstacles as thin as human hair, which debunks that other myth about bats being prone to getting tangled in long hair.

We should be celebrating our little brown bats for one impressive reason alone: they can catch over a thousand insects in one hour. Yes, they eat their body weight in insects! Like hungry Pac-Man’s of the night sky, bats are also critical to pollination and seed dispersal. Farmers and bats can create harmonious relationships with a dual reward: farmers can avoid using pesticides on their crops, and bats can do the dirty work and be well nourished. As opportunistic feeders, bats aren’t fussy with their diet; in fact, they will eat whatever insect species are available in the area.

The little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus), is the most common and widespread of Canada’s 19 species (British Columbia is home to 16 of them). Weighing in at 7 to 14 grams (0.25 to 0.49 ounces) with a wingspan of 22 to 27 cm (8.7 to 10.6 inches), bats are the only mammals who can fly. Found in all provinces and territories except Nunavut, bats are facing a doomsday warning that 99 percent of their population will become extinct in some areas of Canada by 2020. In just three years, a fungal spread of white nose syndrome (Pseudogymnoascus destructans) has decimated the Canadian population by 90 percent.

White nose syndrome (WNS) was first discovered in Canada in 2010. Native to Europe, the lethal fungal disease was found in New York in 2006. Research efforts are focusing on collecting data to determine baseline population numbers to help detect and stop the spread.

The presence of the fungus in the caves and abandoned mines where bats typically hibernate is wiping out entire colonies. The cooler temperatures within those sites are prime conditions for rapid fungal growth and spread. WNS presents as a fuzzy white substance on bat ears, wings and muzzles. The fungal infection, however, also penetrates the muscle tissue and blood vessels of bats, causing them to die of dehydration and starvation; water and electrolytes are lost from their wings and starvation ensues because bats deplete their fat reserves as they wake up more frequently from hibernation to groom.

Though little brown bats like to take up residence in buildings (yes, sometimes house attics, cottages and barns), they also gravitate toward caves and mines—places with high humidity and sanctuary from sub-zero temperatures in winter. During the summer months, maternity colonies, where female bats gather to have their babies, can be found in tree cavities or attics. Bat pregnancy terms are generally six to nine weeks, with a single pup born in June or July, making bats the slowest breeders of all small mammals. The curious pups can fly at three weeks old and are weaned off their mother’s milk in just 26 days.

Although they don’t migrate outside Canada, bats will fly upwards of 1,000 km (621 miles) from summer roosts to hibernation spots called hibernacula. During hibernation, bats can slow their heart rate from 200 to 20 beats per minute to conserve precious energy. Caves can house tens of thousands of hibernating little brown bats. Many return to the same caves, and bat banding initiatives have helped track individual bats who have been recaptured and identified some 30 years later.

Bat banding data continues to demonstrate the effects and spread of WNS and threats to habitat, like wind energy development projects. While disparate banding efforts are ongoing, there is no official coordination program in place to optimize the collected information; however, with the assistance of miners, amateur spelunkers (cave explorers) and the Manitoba Speleological Society (scientific cave study members), researchers have been able to obtain information from previously inaccessible underground locations.

The Wildlife Conservation Society launched a BatCaver citizen science program aimed at cavers and mine enthusiasts in Western Canada in 2015. Volunteers have been instrumental in deploying 50 “bat detectors” to establish recording sites in underground locations. Ultrasound recordings are made throughout hibernation periods and collected in the spring.

In Manitoba, a province with more than 200 catalogued caves, citizen scientists are an integral part of the Neighbourhood Bat Watch. There’s even a Bat Blitz hotline for the public to report observations. The Manitoba Speleological Society also ensures bat well-being by following Manitoba’s bat hibernacula guidelines, which prohibit entry into bat caves from September 15 to May 1. Cavers who have visited caves in parts of Canada, the U.S. or Europe where WNS is present are not permitted to enter Manitoba caves. Per U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service protocols, all the clothes and equipment of researchers who have entered a hibernaculum where WNS is present must be decontaminated before entering other caves, regardless of geography.

In Manitoba, a province with more than 200 catalogued caves, citizen scientists are an integral part of the Neighbourhood Bat Watch. There’s even a Bat Blitz hotline for the public to report observations. The Manitoba Speleological Society also ensures bat well-being by following Manitoba’s bat hibernacula guidelines, which prohibit entry into bat caves from September 15 to May 1. Cavers who have visited caves in parts of Canada, the U.S. or Europe where WNS is present are not permitted to enter Manitoba caves. Per U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service protocols, all the clothes and equipment of researchers who have entered a hibernaculum where WNS is present must be decontaminated before entering other caves, regardless of geography.

The North American Bat Monitoring Program (NABat) is a continent-wide, multi-agency initiative to collect data with maternity colony counts, mobile acoustic surveys and winter hibernaculum counts. NABat hopes to create a database that will determine population viability and also devise conservation measures that are critical to bat health and survival.

Bat citizen science undoubtedly helps fill in knowledge gaps. Free apps like those found on inaturalist.org allow bat enthusiasts to track bats and other wildlife on their smartphones.

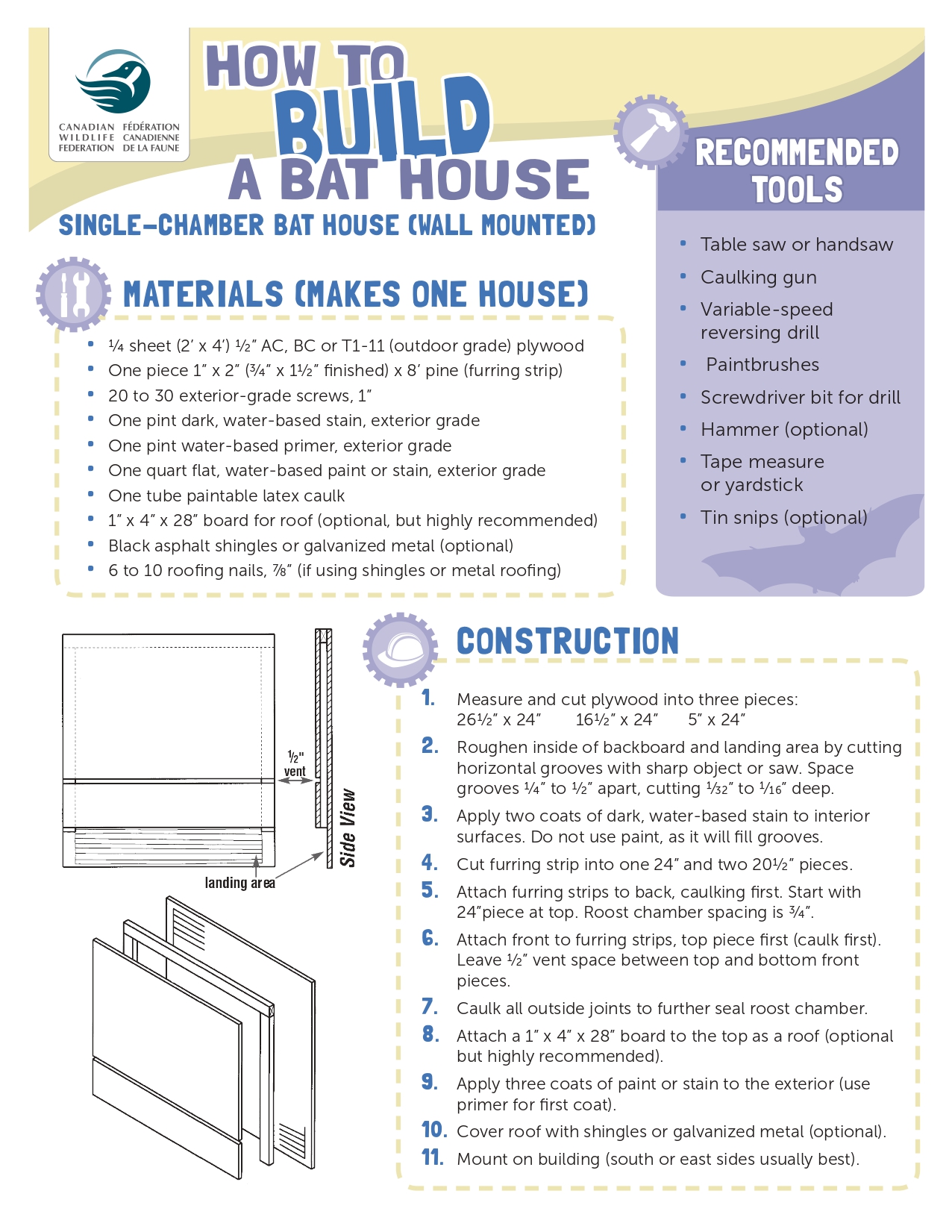

The Canadian Wildlife Federation (CWF) is also connecting with a wide audience through their Help the Bats outreach program. Over 2,000 schools and public groups have been privy to the CWF’s education sessions about bat threats and habitat loss. Through the program, the organization has also distributed 300 free bat boxes (houses) to interested schools and groups. By registering the boxes, students and group members were encouraged to monitor “their” bats and report data. The CWF also had online bat boxes available for purchase, but they quickly sold out, so the organization has provided Harrowsmith with easy-to-build, single-chamber, wall-mounted bat house plans so our readers can construct their own bat boxes. Whether you make the DIY project a neighbourhood effort or a birthday party event (for kids or adults!), building your own bat box is the easiest way to join the movement. For more plans, like a two-chamber rocket bat box and a larger nursery box, visit the CWF website www.cwf-fcf.org or Bat Conservation International’s site at www.batcon.org

Tips to keep your bat company happy

Jules Torti’s work has been published in The Vancouver Sun, The Globe & Mail, travelife, Canadian Running and Coast Mountain Culture. With experiences as a canoe outtripper, outdoor educator, colouring book illustrator and freelancer, she is thrilled to be able to curate, write and read about the very best things in life.