Burnbrae Farms, now in its sixth generation of farming, is one of the largest egg producers in Canada.

Here, they share how strong family values, calculated risks and effective succession planning helped them become one of the country’s most thriving agricultural family dynasties.

A STORY STEEPED IN TRADITION

When you ask Margaret Hudson, President and CEO of Burnbrae Farms, the secret to their family’s success, her answers come quickly and knowingly: “It was our father’s vision, a lot of hard work and everyone’s dedication to our family’s values instilled by our father and the strong women who influenced him from the very beginning.”

Of course, the Hudsons’ journey to becoming a leader in Canadian agribusiness was not a simple one (think World Wars, a depression, a pandemic, etc.); however, tradition acted as an adhesive. “One thing each generation carries from one to the next is a closeness as a family,” says Sue Hudson, Burnbrae’s Communications and Digital Marketing Director. “The reason why our generation is able to lead the company as a group of siblings is because we have a bond, and we are working to create a similar bond through shared experiences for the next generation.”

ACROSS THE POND

The Burnbrae Farms story begins when 17-year-old Joseph Hudson immigrated to Canada from Scotland in 1874 with his parents, Joseph Senior and Margaret Hudson, along with five of his siblings. While his parents settled in Soperton, ON, and started farming and milking Ayrshire cattle (ironically named after where Joseph Senior and Margaret came from in Scotland). Joseph headed to Manitoba, possibly because of the economic boom caused by the expansion of the CP Railway. There he married Jean Thompson. The couple had three children: Lillian, Mareta and Arthur Joseph (AJ). In 1884, Joseph Senior passed away—Joseph moved his family to his parents’ farm in Soperton. On March 23, 1891, after selling his father’s dairy farm, Joseph & Jean paid $2,150 for 44 acres of land just north of Lyn, ON, and named the homestead Burnbrae Farms, loosely meaning “hillside stream” in Scottish.

COWS RULE THE ROOST (FOR NOW)

As was customary at the time, Joseph and Jean’s only son, AJ, received ownership of the family farm in 1922, when he was 28 years old. He and his wife, Mary “Evelyn” Purvis, whom he had married a few years earlier, had five children—Helen, Jean, Grant, Frances and Joseph (Joe). Life at Burnbrae Farms went on happily tending to the cattle, still the main focus of the business. Soon, however, World War II and the Great Depression would drastically transform the history of Canada, and the agriculture industry, like most, would be hit by severe hardships like farm foreclosures and rural poverty, leading to the implementation of government programs aimed at stabilizing the sector and providing support to struggling farmers.

A NEW IDEA IS HATCHED

As mentioned, AJ and Evelyn’s children grew up during trying times. However, the Hudsons kept Burnbrae Farms afloat, thanks to a little side business utilizing a gravel quarry on the property. The family all worked hard on the farm, with kids doing chores before and after going to school. Everyone chipped in at home, and charity work was always a big part of being a Hudson, as was attending church and supporting the local community.

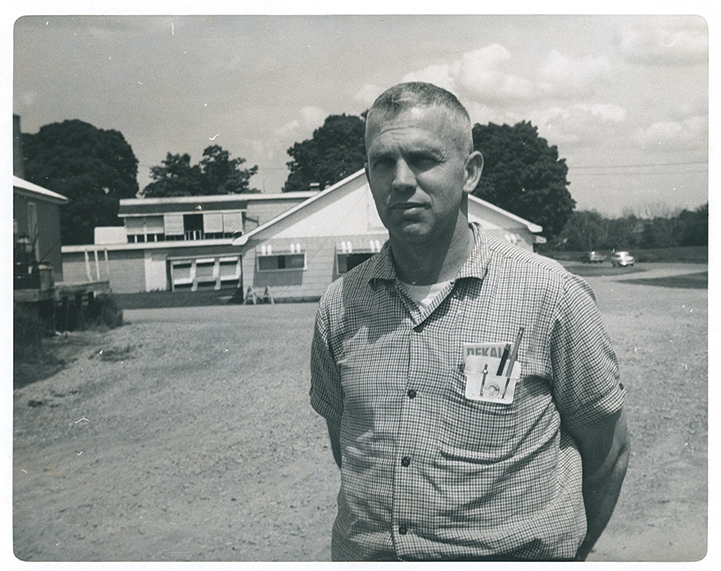

Eventually, AJ’s sons, Grant and young Joe, naturally stepped into the family business. The farm grew to 140 acres and included cash crops in addition to the dairy herd. But a seed was planted in Joe’s mind in 1943 when he was still in high school: At the age of 14, he did a project on raising chickens for egg production for an agriculture class and purchased 50 leghorn chicks. To this day, the family refers to this pivotal shift in the farm’s history as “The 50 Chickens.” As a result of this project, Joe and Grant added egg farming as a side business to Burnbrae Farms, spearheaded by young Joe, but, as you may have guessed, eggs wouldn’t stay on the back burner for long.

During WWII food shortages were an issue in Europe. Eggs were being dried in North America and shipped overseas to feed people. Joe was deeply affected by the war and saw this as an opportunity to help others, and to generate additional needed income to expand the farm.

By the end of the war – around the same time Joe graduated from high school – egg production was more profitable than dairy farming for the Hudsons and Joe, with the help of his brother, Grant, and his father, AJ, began to expand the business.

By the late ’50s, both brothers were married: Joe to Mary Morwick; Grant to Beryl Hick. They transitioned out of dairy cattle and into beef cattle, but eventually Burnbrae Farms’ focus officially became poultry. In 1959, Burnbrae was incorporated as a company under the name Burnbrae Farms Limited with Joe’s father, AJ Hudson, as President. From this time forward, Burnbrae’s future was firmly aligned with egg production. “Dad was a visionary,” Margaret says, alluding to the fact that her father was more than a farmer content to run the family business as it had existed for almost 50 years. “And he was a risk taker. In his earlier years, he unequivocally shaped the business.”

And once the poultry business started to show real growth, “Joe the Visionary” took over. Instead of challenges, he saw opportunities. He and Grant were expanding and building new chicken barns at such a rate, they had their own construction crew and building supply store where they sold lumber under the name “Hudson Brothers.” He was able to stay one step ahead of the curve as their business grew, acquiring grading stations (facilities with machines used for washing and sorting eggs into different grades by weight) and processing plants. Joe was an early adopter of new technological advancements to streamline processes and develop new products. He was always looking to upscale grading equipment, and he introduced egg pasteurization as well as hard-cooking and patties and omelettes. (Egg-whites only sold in cartons, ready-to-eat boiled eggs, pre-made frozen egg patties, egg bites? You can thank Joe for those.)

“He was shaping the business with the decisions he was making,” Margaret says. “But once he grew it to this much larger size, there were more demands on him. The approach to running the business needed to transition from being entirely entrepreneurial— taking risks and creating a vision—to learning how to scale and manage a much larger company.” Thankfully, help wasn’t hard to find: In addition to supplying many jobs to local workers, Joe and Mary had five children— Helen Anne, Mary Jean, Ted, Sue and Margaret

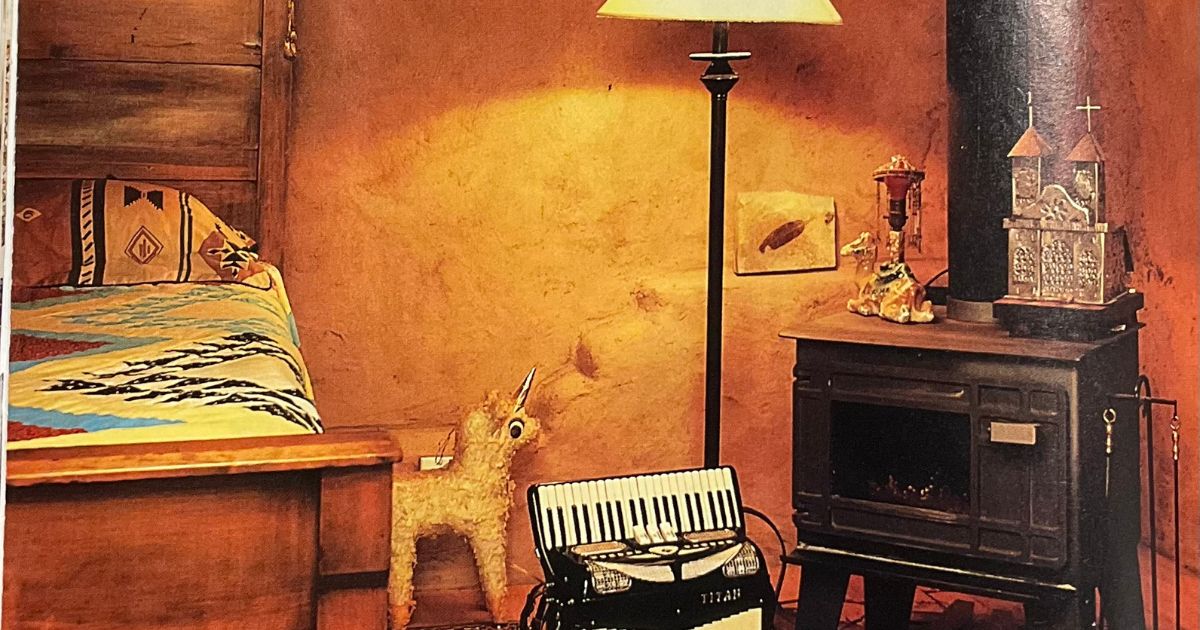

(friend). Back Row left, to right: Jean, Joseph, AJ, Evelyn

BREAKING THE MOULD

“In 2006, Dad began the move to turn the farm over to the next generation,” Sue says, referring to the five children. Just like the generations before them, the Hudson children were brought up in the business. As early as their childhood in the 1960s and on, they were expected to work in the business and on the farm and were privy to the rapid growth of the egg business. During the 1960s, Burnbrae Farms expanded its operations, investing in modern egg production techniques which helped bolster egg production in Canada and the world to feed growing populations. These new systems revolutionized the industry. (In true entrepreneurial spirit, Joe had hedged his bet in order that he would either have the scale to compete with the American farmers, or be one of the largest egg farmers in Canada during a period of change in the Canadian agricultural egg industry.) In the 1970s, the company continued to expand and solidified its position as a leading supplier of eggs in Canada. By the 1980s, Burnbrae Farms had become one of the largest egg producers and graders in Canada, leveraging technological advancements and sustainable farming practices to set an example for the egg industry and agricultural businesses across the country.

Those were all admiral achievements, but the Hudsons’ most revolutionary action was about to happen. “Our father had so many incredible matriarchal role models, from our grandmother Evelyn to Aunt Lil to our mother” Margaret says. “It’s great to have these role models that inspire you and make you feel like you can do anything. I believe it’s because of all these strong women’s influences that he gave equal opportunity to all his children. In the past, the business only went to men, but he transitioned it to all his children, including his daughters. He broke that tradition and started a new one.”

Another reason why this is key to Burnbrae Farms’ story – and the history of Canada’s agricultural industry as a whole – is because, in 2008, Margaret was named President of Burnbrae Farms (the title of CEO followed in 2020), making her one of the first women to lead a major farming dynasty. “A few of us from our generation joined the business in the late 80s and early 90s,” Margaret recalls. Today, Ted Hudson (Joe’s son) is Executive Vice President, Business Development & Poultry Industry Relations and Ian McFall (Joe’s son-in-law) is Executive Vice President, Foodservice, Industrial Sales & Government Relations. “Dad was in his sixties when he embarked on his strategy to make his dream of a national company come to life. He started his western expansion a few years later with the purchase of the Safeway Winnipeg grading station, and we were already in the background when the acquisition happened. We moved in to help with the integration. I think it’s one of the key moments of our family’s story because up until then he was wondering whether his kids were going to take a serious interest. It was at that point that his succession plan started to become a reality and he embarked on his plan to be truly national.”

Margaret and Sue recall the conversations about who was going to go into the family business starting when they were very young, but really escalating when they were university aged. The planning was completed in their 30s and 40s and the full transition of operational control happened in 2011 when their dad was in his 80s. And while the business education was important, the family attributes the traditions created by their mother and other strong women for their closeness as a shareholder group now.

For generations, the family has gathered for all major holidays and celebrations. “These gatherings were important to our parents, but especially to our mother,” Margaret recalls. “We would have these great big family meals and all of the generations would come.” Adds Sue, “And continuing today, it’s not uncommon to have 30 people for Thanksgiving or Christmas dinner, and our sister Mary Jean makes sure all the family recipes and place settings are there.” Christmas 2023 was the last holiday they had with their father, Joe, who passed away on March 14 at the age of 94.

DINNERS AND DOGS

Meanwhile, the newest generation is coming of age. (Helen Anne Hudson and Vincent Guyonnet’s children: Allister, Tristan and Audrey (Guyonnet); Ian and Mary Jean McFall’s children: John, Will and Hugh; Ted and Sherri Hudson’s children: Catherine and Joseph Thomas; Margaret Hudson’s children: Evelyn and James Rogan.) Joe & Mary’s children are proudly committed to ensuring the success of Burnbrae Farms by relying on what their ancestors taught them. “The most important part that you need to take care of in the transition of a family business is just that—family,” Margaret says. “Shared experiences and shared values are absolutely critical if you’re going to expect family members to continue to want to own it together.”

For the Hudsons, in addition to annual celebrations, those experiences included family ski trips to the Laurentians when we were younger. “My dad took up skiing later in life. He would rent a chalet, and we’d all bring friends. There would be a lot of people, all different ages, playing board games and just having a great time together,” Margaret recalls. The family cares about carrying on these traditions and enjoys creating new ones. They now also relish spending time at “The Ski-Doo Shack,” a little structure built by their brother Ted on 1,000-acres of their land. Of course, hiking back there with the dogs is popular with most, rewarded with a bonfire upon arrival. “On one occasion, Margaret and a few others got lost going up to the Ski-Doo Shack, and it was like Survivor,” Sue laughs. “We sent Rufus, Ted’s Australian Shepherd, to go find them.” Taking walks back the barn road on the farm is another family favourite, often accompanied by five or more dogs and sometimes their sister Helen Anne will bring a horse along as well.

These shared experiences are critical to moving the business to the next generation, especially when these cousins will both own the family business and work together. “These activities are very important to us personally as we enjoy spending time together, especially on the farm, but also to the business to help with a smoother intergenerational transition,” Margaret says, “and they are truly a legacy left by our mother and other strong female role models.”

GENERATION ALPHA + (eventually) BETA

“I mean, G6 is under 10 years old,” Margaret says. That list, so far, includes Will & Brei McFall’s children: Charlotte, William and Penelope; and John McFall & Emily McInnis’ child: Maxwell McFall. “So that’s a story yet to be written. And, yes, there is an expectation that the ownership of the business will carry on in some capacity within the family, depending entirely on the interest and abilities of the next generation.” If you consider that multigenerational businesses like Burnbrae Farms play a significant role in Canada’s economy and contribute to its cultural and social fabric by preserving traditions and passing down expertise from one generation to the next, we can’t wait to watch history unfold as these little farmers grow to fill these rather large boots.

Three Tips For Succession Planning

1 Start the conversation with the next generation early. We’ve chosen to start conversations around the business when the children are young: Older than five years old but younger than 10.

2 Use a Family Advisor: Someone who specializes in working with families through intergenerational transitions. We established a Family Council when the G5s were young, working with our Family Advisor, meeting annually as a business family.

3 Develop Shared Values through Shared Experiences. It’s critical to spend time together as a family so that shared values can be developed. Strong relationships will be needed to navigate conflict as a business, and this work needs to become more intentional with cousins versus siblings.

Having had the privilege of being at the helm of numerous national magazines, including Chatelaine and Today's Parent, Karine is passionate about content and building strong communities. Her 30+years working in the magazine industry in Canada and the U.S. have allowed her to develop an editorial vision that focuses on exceptional story-telling, dynamic media packages, successful brand partnerships and robust digital strategies, all with the audience's wants and needs top of mind. Karine enjoys collaborating with her team, clients and members of the community, so please do not hesitate to reach out to her.