By Nigel Moore and Jade Zavarella

A decades-long infection of colonialism and ignorance makes real progress toward reconciliation a difficult task. The provision of reliable energy is one arena where concrete steps can be taken immediately to provide a foundation for building better lives.

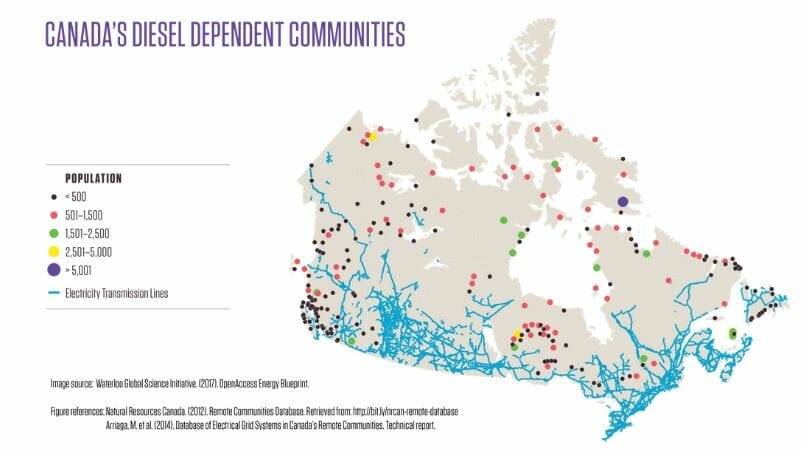

The present situation is this: There are approximately 300 communities in this country that, as a result of their remoteness and small populations, are not connected to the electricity grid. Two-thirds of the people living in these communities are indigenous. The majority of the energy that they rely on for electricity (99.5 percent) and heat (84 percent) comes from fossil fuels (primarily diesel).

Something else you should know: Indigenous peoples constitute the fastest-growing segment of the Canadian population.

Climate change and diesel pollution

Fuel must be transported to remote communities at great expense. Roadways are the most inexpensive option, when it’s possible. But climate change is making this increasingly difficult, as the ice roads that are often relied upon become impassable due to warming. When this happens, often the only solution is to fly the fuel in by air. That can more than double total energy costs.

Canadians living on-grid complain bitterly about single-digit percent increases in cost. Imagine if your energy costs doubled overnight when you could barely afford to heat your Arctic home in the first place?

Burning diesel is also a cause of climate change itself. While the contribution of overall Canadian greenhouse gas emissions from off-grid communities is negligible, diesel emissions in areas of snow cover contribute to additional regional warming. The deposition of black carbon (soot) particles on white snow results in faster melting rates.

Diesel generators not only pollute the air with their toxic gases and smell, but also are a nuisance with around-the-clock noise. Diesel is also the No. 1 cause of toxic spills in remote communities. Unfortunately, governments do not have a good track record of cleaning these up.

Generators also create increased fire risk. Indigenous people face a 10-times greater chance of dying in a fire as a result of their proximity to aging diesel generators.

Blackouts and load restriction

In most diesel-dependent communities, the dirty energy provided is simply not enough to meet their most basic needs. Undersize and aging generators are to blame for frequent blackouts that can last for days. The result is food spoilage, health-care centres with no electricity, schools with no electricity, and homes with no electricity.

In fact, 25 to 50 percent of the communities (the figures may be higher, as we don’t have reliable data yet) are deemed to be in “load restriction status.” The term means that the generators are consistently operating at their maximum capacity. No new homes can be built and connected to the system. No new energy consuming businesses can be created. This is but one reason why some extended families are forced to share small uninsulated homes with no power or running water.

How are young people—who are the majority of the population in many places—expected to develop their ambition and dreams under these circumstances? It is not a stretch to point fingers at the strangling effect of energy poverty on quality of life in such communities as a direct contributor to the youth suicide epidemic. Canada’s ignorance in supporting the basic necessities of indigenous people is a national shame.

Costs

Providing energy to communities that are geographically isolated almost always comes at a higher cost than it does in densely populated areas. Does this mean that off-grid communities should be abandoned and residents forced to relocate? Of course not.

But costs are still a huge barrier to change. Large subsidies are provided to help cover energy prices that can be 10 times more expensive than in the rest of Canada. Any upgrades to systems requires a much greater logistical effort than in grid-connected areas.

If we are to minimize costs, we must look to the future and adopt a holistic view. We know that the direct costs of diesel provision will increase due to climate change and carbon policy. Diesel price spikes will continue to be a risk. There are also indirect costs due to chronic health issues linked to pollution and the sick being treated in health-care centres that suffer frequent blackouts. And costs for site remediation due to diesel spills are already estimated in the tens of millions.

Add in opportunity costs, an important calculation in sound policy making. Any new economically productive activities will be severely constrained by load restriction. Another generation will be lost to the effects of energy poverty. What might they have been able to contribute had they been given a chance?

But the human costs are the most daunting. The suffocation of hope and further entrenchment of mistrust between indigenous people and the rest of this country are beyond calculation.

Renewable energy

Despite decades of jurisdictional foot dragging by both provincial and federal governments, hope is on the horizon. The costs of solar, wind and energy storage are dropping rapidly and will continue to do so. In remote communities, the fact that renewables use locally available energy sources presents a viable, cost-effective opportunity.

As a result, several indigenous communities and Canadian cleantech innovators are recognizing that steep upfront costs can be justified by savings over time and improvements to quality of life.

In Colville Lake, Northwest Territorries, a solar backup system has reduced blackouts from weekly occurrences to an annual one. In Deer Lake, Ontario, a solar system installation at an elementary school has cut the community’s annual energy bill by $92,000 and created employment opportunities.

The Hupacasath First Nation in British Columbia now powers over 6,000 homes with a run-of-river hydro projects. As a result of that success, Hupacasath First Nation has developed a tool kit for other communities to use in developing their own renewable-energy projects. A number of other capacity-building projects are helping to equip a new generation of indigenous clean-energy champions across the country.

These success stories are emerging despite a lack of funding or policy push from the outside. They have come about because the cost of alternative solutions is now affordable. The application of renewable energy is aligned with deeply held indigenous values of self-determination and environmental stewardship. These are real solutions.

Our opportunity

Canadian policy-makers have by and large endorsed the idea of creating a green economy. Our governments have committed to spending billions on clean-energy infrastructure over the coming decades in order to create a more inclusive and resilient society that will benefit all Canadians. This is a critical development when it comes to alleviating energy poverty in Canada because it means that the narrow question of cost has now become a broader question of scope.

If we are indeed building a green economy, whom will it serve? Or to put it more bluntly, where will we spend the money? Will we use our green infrastructure funds to improve the lives of those who stand the most to gain from access to renewable energy? Will we put the fastest-growing segment of the Canadian population at the forefront of our efforts to train a workforce for the green economy?

Will we recognize that consigning off-grid communities to another lost generation is a choice, now that we know we have the means to take action?