It’s 11 p.m., bitterly cold outside, and the snow has stopped after three or four hours of accumulation. A sensible person would be heading to bed at this point, but I am not a sensible person. I put on my coat and boots, grab my shovel, and head outside to clear my backyard rink.

If I don’t get the snow off immediately, it could stick to the ice and ruin the skating surface when the temperature rises tomorrow. I’d have to flood two or three times to smooth things out, and if there’s a breeze while I’m doing this, I may end up making things worse. My fingers will be numb after 20 or so minutes, and I know I’ll be tired at work tomorrow. Why do I do this to myself?

My reasons for rink building are complicated and go back almost 30 years. For one magical winter in my childhood, two of the neighbourhood dads came to an arrangement with the city: they would build a public rink in the park behind their houses, and the municipality would pay the water bill. Not a bad deal, but the real winners were us kids. We played on that rink for hours and hours, until we were so cold that we couldn’t feel our toes. We didn’t care. Out on that rink we were totally free. No coaches to admonish us for a fancy drop pass or failed dangle; no adults to tell us to play safe or be quiet. We were governed only by the limits of our energy, creativity and a simple social contract: no equipment means no slapshots, and everyone gets to play. Ken Dryden was absolutely right when he said that the golden age of hockey was whenever you were 12 years old. After that winter, I quietly resolved to build my own backyard rink when I grew up.

If my nostalgia for the outdoor rink of my childhood sounds a bit clichéd, that’s probably because it is. Several years ago, before I actually tried my hand at rink building, I did a study of Canadian hockey novels and wrote a book on this subject. One of the things I found was that hockey literature tends to mythologize the backyard rink as a place of beauty, innocence, purity and nostalgia, often in contrast to the corrupting or complicating influences of pressure and money in the organized game or to the artificiality and “unnaturalness” of indoor ice. The first known reference to hockey in Canadian literature is from Samuel Chandler Haliburton’s 1843 novel, The Attaché; or, Sam Slick in England, which describes boys “hollerin’ and whoopin’” as they play “hurley on the long pond on the ice.” This expression of childhood fun and innocence sets the tone for many similar passages to follow, and certainly resonates with my own childhood memories of the neighbourhood rink.

There are limitations to these depictions, and frequent repetition threatens to render them banal. Nonetheless, as I encountered scene after scene of romanticized pond-hockey purity in the novels I was reading and writing about, that vivid and unique feeling from my own memories of the outdoor rink kept coming back. Could the rink truly have been that freeing and fun? Eventually, I had to find out: it was time to make good on my rink-building resolution.

Having now spent three winters and countless hours planning, building, shovelling, resurfacing, repairing, draining, disassembling, storing and sometimes even skating on my own backyard rink, I have a pretty credible theory as to why that magical neighbourhood rink from my childhood only lasted one winter: the two dads who built it probably gave up due to some combination of frostbite and exhaustion.

Hockey novels typically don’t recognize the amount of effort that goes into rink building, so despite having read a great deal on the subject, the first thing I realized was that I had no idea how to actually build a rink. After a few hours on the internet I figured out the basics and eventually settled on the “above-ground pool” approach in which a wooden frame is used to hold water on top of a gigantic tarp. I bought enough lumber for a 48- by 32-foot periphery, then set this up by screwing the frame together and driving stakes around the outside of the frame at four-foot intervals to support the weight of the water. After procuring a gigantic 60- by 40-foot tarp that I can barely even lift, I positioned this over the frame and then turned the hose on it for approximately 12 hours. After a few nights of good, solid –15°C (5°F) cold, we were ready to skate.

This all sounds fairly straight forward in summary, but actually doing it was full of decisions and challenges. Rink building is the DIYer’s dream: there are many ways to build one, no two are the same, and there are plenty of opportunities for creative customization and problem solving. How am I going to deal with the slope of my backyard? Can I stop pucks from flying out into the corn field behind the rink? How will I protect the tarp? What will I do for lighting? How am I going to resurface the ice? One of the more practical pleasures of rink building was figuring out solutions to these problems and opportunities, ideally with materials that I already had lying around the garage.

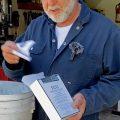

The challenge I took most pleasure in solving was the question of how to resurface the ice. My rink is far back enough from the house to make messing around with a hose impractical, and I don’t have a lawn tractor or wagon to pursue some of the more exotic resurfacing options that I found on the internet. After a bit of thought and planning, I ended up building what may be the world’s first backpack Zamboni. After fashioning a large T-shaped rake out of some PVC pipe, I drilled holes in the flat end of the T and attached an on/off valve at the pointy end. I hooked this valve into some flexible rubber pipe, which was in turn connected to a 23-litre (six gallon) pail that I drilled through near the bottom and added a plastic drainage valve. Taken together, this all amounts to a gravity-powered reservoir and drainage system that—when the pail is filled with water and mounted on an old backpack so I can easily carry it—trickles water down through the flat end of the PVC “T” and out onto the ice. It’s a little bulky, but it works fairly well and was quite fun to make. It has also turned out to be a great conversation starter; as it happens, people are surprisingly interested in backpack Zambonis.

It’s now past midnight and I’m done shovelling the rink. My bed beckons and tomorrow morning draws near, but the ice makes an argument so beautiful and compelling that I lace up my skates. The sky is clear, the stars are out, and my breath hangs hauntingly in the air before dissipating into the dark. I step onto the ice, and immediately I’m going fast. Adult life is cluttered with worries and responsibilities, but out here I’m free to be entirely in the moment for at least a few precious minutes. I take slapshots, searching for that elusive top corner, and no one is around to watch me miss. With the moon and stars reflecting off a blanket of snow, the winter night is somehow more hospitable than the deeper darkness of summer. Nonetheless, it’s hard to feel entirely welcome. This mild and curious alienation is part of the appeal, and moving quickly in a setting that instinctively calls for caution is both exhilarating and disorienting. The ice is hard and mysterious, gauzy and opaque in the moonlight, and it feels thrilling to intrude on what poet Charles G.D. Roberts called the “white, inviolate solitude” of the winter night. I don’t want to exaggerate or overstate this claim, but skating outdoors at night is an entirely unique and singular feeling. Experiences such as this with no obvious analogue or correlative are rare, and this scarcity is yet another pleasure of the outdoor rink.

Saturday arrives, and the whole family is out skating. My younger son pretends to be Auston Matthews. He takes a tenuous pass from his older brother, redirects it toward the net, and then falls down. “Matthews has done it! The Leafs win the Cup!” For a moment I become that little boy from almost 30 years ago, pretending to be Wendel Clark and that I just won the Stanley Cup. (I know, I know—I did say I was pretending). At the same time, though, I’m still my adult self, watching my son celebrate his imaginary win. The moment isn’t about longing; I realized a long time ago that I’ll never win the Cup. Rather, it’s a flood of warmth, awe, gratitude and contentment. It’s OK that I’ll never win the Cup; my life turned out to be pretty great anyways.

This is why I ultimately keep putting in the effort and withstanding the elements to build and maintain our backyard rink. I want to create an opportunity for my kids to inhabit the wonderful emotional space that I remember so vividly, the rink as a theatre of heightened freedom, creativity, imagination and excitement. The real joy for me is to tag along as they skate around and revel in it.

Looks like more snow in the forecast, so I’ll probably be up late again shovelling. And my back is already sore, because this year I’m teaching my three-year-old daughter how to skate. I wouldn’t have it any other way.