The tall tale behind one of the oldest homes in Laval, Quebec.

The former farmhouse now known as Therrien House was built around 1722 in St-François district of Laval, Quebec’s third-largest city. It is believed to be one of the oldest homes on this island located just north of Montreal and bordered by the Des Prairies and Mille-Îles rivers. Historical records reveal that the original inhabitant, Pierre Beauchamp, a carpenter, was given the land by the Séminaire de Québec in 1718 and he himself built the house. In 1846, Charles Therrien acquired the house and the adjacent agricultural fields. For 140 years, several generations of the Therrien family occupied this fieldstone home, hence the name Therrien House.

To this day, a large part of the land surrounding the house, which faces the Mille-Îles River, is still used for growing crops. On August 28, 1974, the house was designated a historical monument by the Quebec Ministry of Cultural Affairs. This part of Laval, with its wide open spaces, provides the perfect rural setting for this type of old house. And because of these surroundings, it’s easy to imagine the sounds made almost three centuries ago in the fields, of horses and other livestock, and the thunderous roar of trees being felled by axe for firewood and to clear the land for planting crops.

In his book Laval: Une histoire d’appartenance, historian Marcel Paquette writes that in the 1970s, at the request of the Société d’histoire de L’île Jésus (Laval), archaeological searches were undertaken not too far from where this house stands at the most easterly point of the island. Some arrowhead tips and the vestiges of an old aboriginal settlement camp were uncovered. But in spite of these remarkable discoveries, no other efforts were ever expended to further exploit the dig site.

The present owners, Daniel and Chantal, purchased the house in 2006. While showing me around their property, after I had scouted it for possible inclusion in my photo book, Old Homes of Quebec, they told me a fact about this house, which conjured in my mind an incredible image. Sometime in the early 1700s, the house came under attack by the Iroquois feuding with the settlers in this area of the island at the time. Upstairs in the master bedroom, there’s a mezzanine, which now serves as the exercise room, and there you can get a good close-up view of the underside of the original roof boards that are laid bare, just like when they were first installed.

Upon closer inspection of these boards, and incredulous as it may seem and sound, especially since we’re talking about an event that happened almost 300 years ago, the actual holes and black scorch marks left by two flaming arrows that had hit their mark and pierced through the roof are still visible. “How is this possible?” I asked the owner. Chantal explained that when she and Danielrenovated the roof, they were able to restore and keep the original boards intact and exposed because they opted to solidify and insulate the roof, which is covered with cedar shingles from the outside, as all the previous owners had done.

Another peculiar and fascinating aspect about this house, which is not readily apparent at first glance, is that when you’re standing on the front lawn looking at the house, one automatically perceives it as being the façade. In fact, you are actually seeing the rear of the house, as it was constructed to be back in the day.

For as the rural population expanded in Laval and elsewhere, a continuous road system that could connect the different municipalities together had to be developed and maintained. So some municipalities and towns either expropriated or bought parts of the land from the property owners to reconfigure or extend the road.

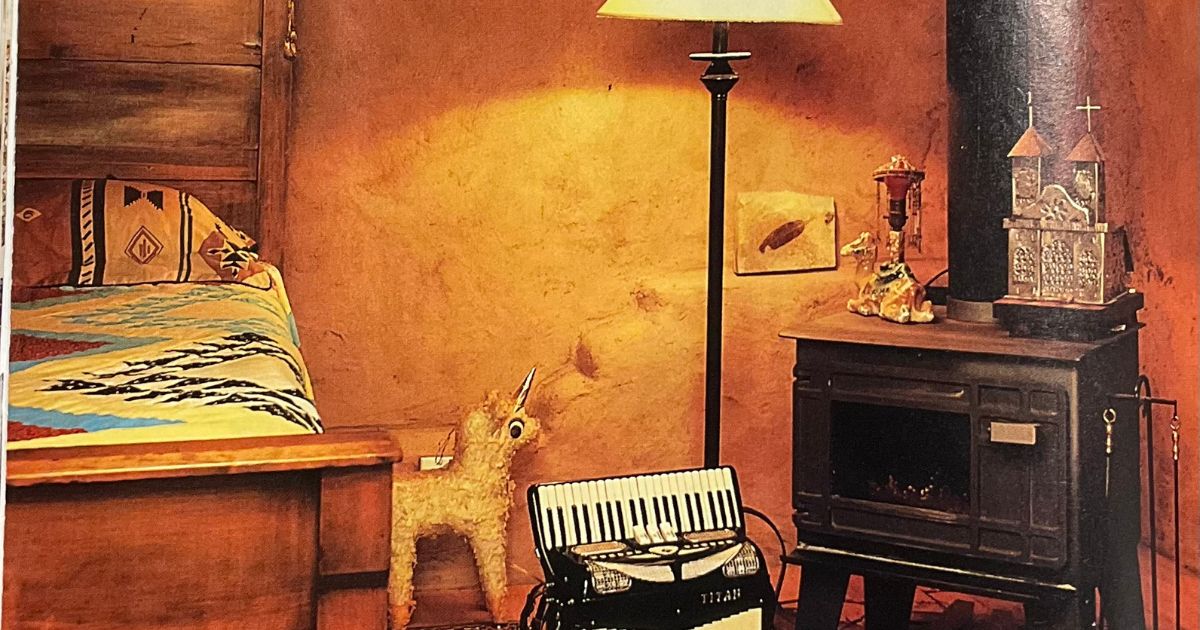

This home, as with a few others I encountered, had to either substitute the back of the house for the front, which is the case here, or vice versa. Other owners had no choice but to move their house back from the side of the new road, because it was now too close for comfort. To the right of the main house, the extension that was added about five years ago is today used as the main entrance, which opens into the new kitchen. The former occupants, I was told, used the fireplace in the dining area to do all their cooking.

Now the fireplace is where tall tales are shared, of flaming arrows and the organization of archaeological digs in the hopes of unearthing more stories.

Born in Montreal, Perry Mastrovito is an award-winning professional photographer for over 35 years and lives in Laval, Quebec. Inspired from his youth by natural and built environments, Perry pursued his photographic passion by studying graphic arts, printing and commercial photography before starting his career.

Mainly using natural light and graphic compositions to create his images, Perry specializes in photographing facades and interiors of the most beautiful contemporary and old houses in Quebec, log and one-room log homes, as well as gardens. private and regional landscapes. He also enjoys exploring other subjects, and creating in his studio and around the world (37 countries to date), conceptual and editorial images which are represented by several Canadian, American and European photo agencies.