We are now becoming use to the early night fall, and late morning light. It is curious that if we go south to enjoy its warmer climate, we notice that night falls earlier than we might expect given the tropical location. For Canadian summers, sunset is in the late evening, not the earlier evening we might currently experience in the Caribbean.

When I was developing lighting guidelines that minimize the impact of artificial light at night on ecosystems, I looked into the variation in the length of day, and the length of night throughout the year. These proved to be very important for the viability of most species. Canada’s mid-latitudes with seasonal changes in daylight make our country a good laboratory to study these effects and give us the contrast between our Canadian seasons.

Canada’s great diversity in plants and animals is partially due to the country’s extent in latitude: from effectively the northern limit of the Northwest Passage at +75° down to 50° across the prairies, and 42° in southern Ontario (Point Pelee National Park, bird sanctuary and Dark Sky Preserve). This range of 35° has impacted the ecology of wildlife and the cultures of its indigenous peoples.

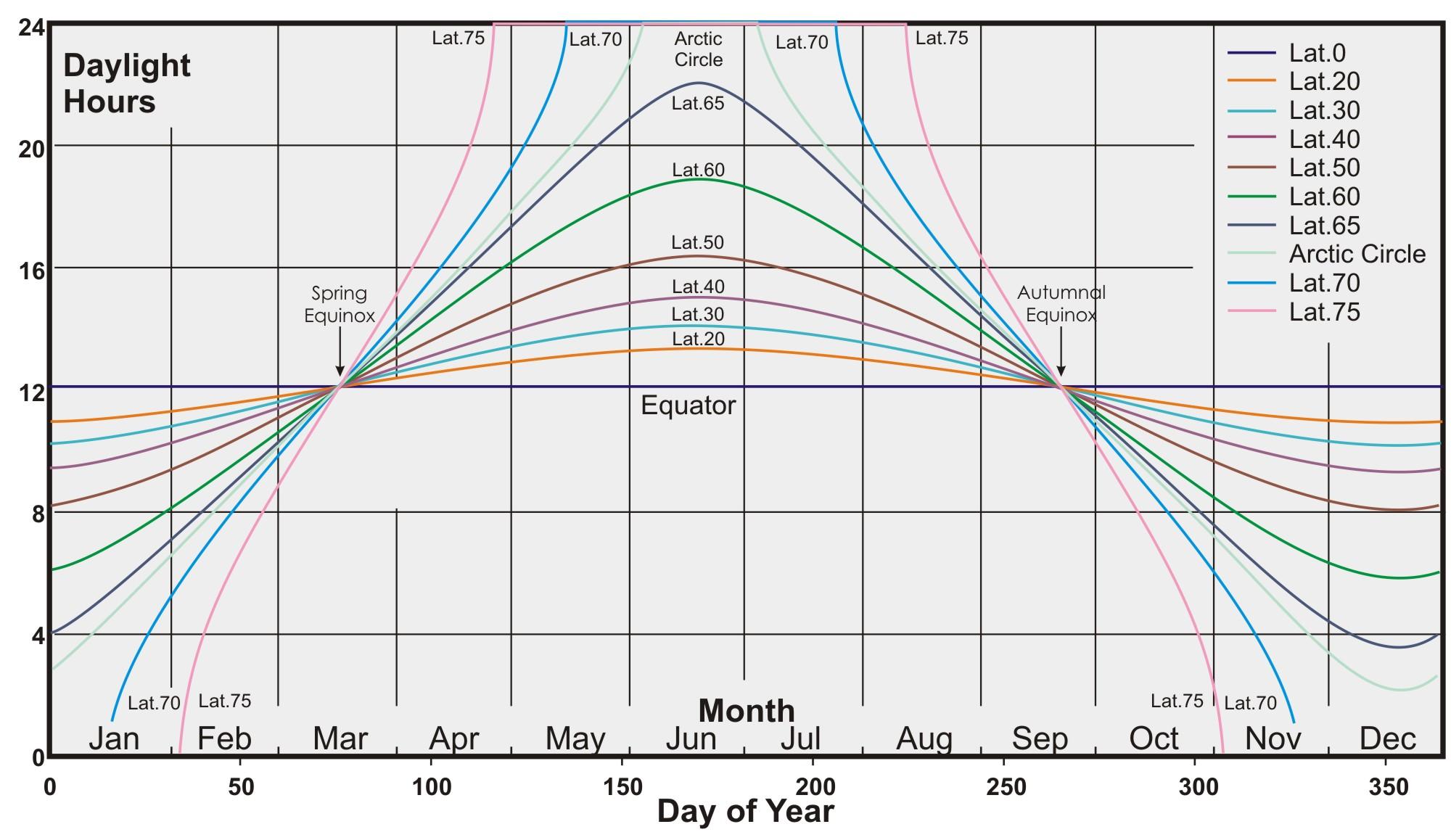

It is interesting to contrast the daylight hours in the Caribbean and Canada using the accompanying graph. Our seasons are due to the wide range in the length of time the Sun is in the daytime sky, which provides daytime heating. The equatorial countries see almost no variation in daylight over the year, and daylight hours are about the same length as for night. If we include twilight then tropical life has roughly 13-hours of usable daylight. In Canada, it ranges from no daylight up to 24-hour daylight. We have much more sunlight in summer, though the cost of this bounty is the short daylight of winter.

I have plotted the total daylight hours for a range of latitudes from the equator up to +75º. Below latitude 40º there is not much change, but for Canada, the swing between summer and winter is extreme from about 10 to 15 hours for southern Ontario (including twilight), and 9 to 17 hours for Edmonton. This will not surprise most readers, however the figure shows a couple of other interesting details.

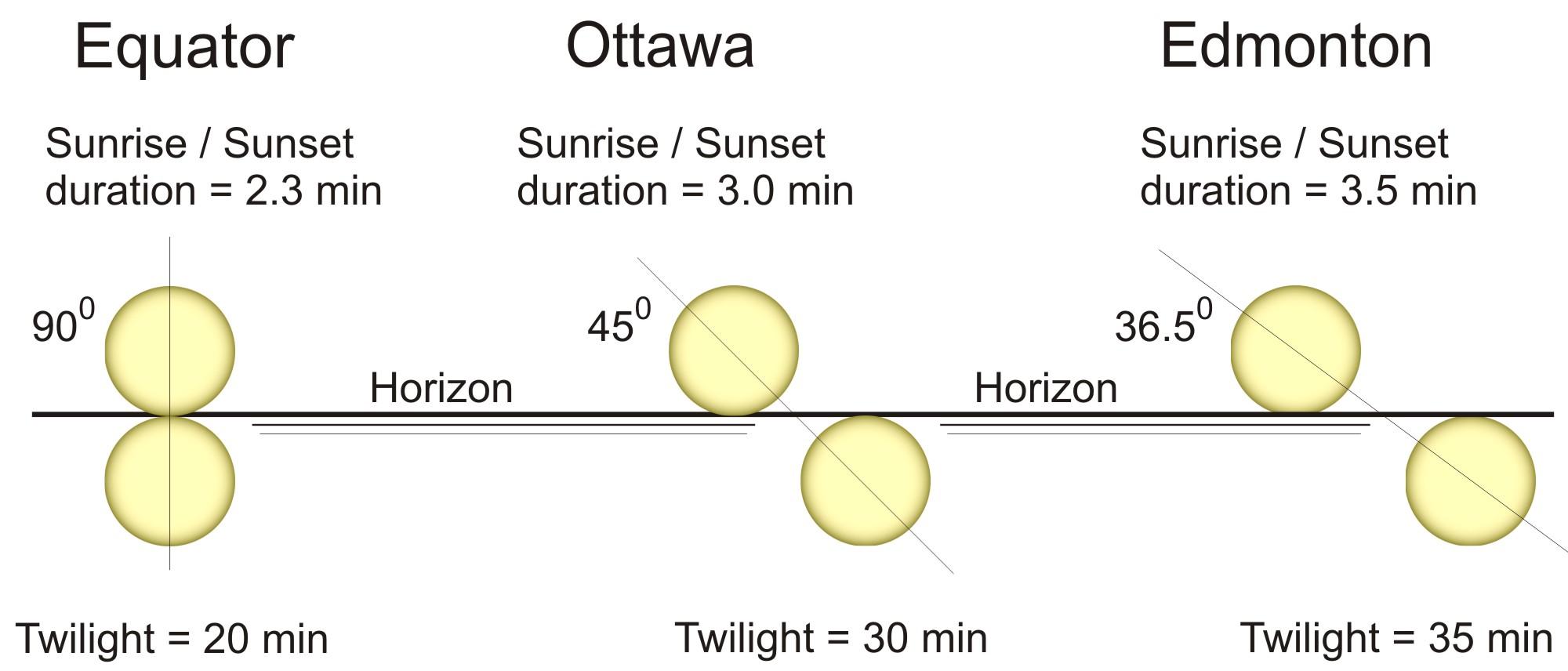

The most obvious feature is that all latitudes have 12-hour days near the equinoxes. It is not exactly 12 hours because it takes a minute or so for the upper limb of the Sun to set below the horizon – and this translates into a delay in the date for 12-hour daylight. And, it takes another 30-minutes or so for twilight to fade into night – extending our usable daylight by about an hour each day. Indeed, for most of the year our “rush-hour” traffic is during daylight!

The angle at which the Sun passes below the horizon – extending daylight, also depends on your latitude. On the equinoxes, from Ottawa the Sun appears to move at 45º to the horizon and 6º shallower at the summer and winter solstice. But Edmonton, at +53.5º latitude, looses the Sun at a shallower angle – only 36.5º, and this lessens to only 29º in The angle at which the Sun passes below the horizon – extending daylight, also depends on your latitude. On the equinoxes, from Ottawa the Sun appears to move at 45º to the horizon and 6º shallower at the summer and winter solstice. But Edmonton, at +53.5º latitude, looses the Sun at a shallower angle – only 36.5º, and this lessens to only 29º in summer and winter.

In the past with only the Sun ad firelight to illuminate our world, these seasonal changes in daylight were critical. However, these days with artificial lighting the activity of most people is no longer based on daylight. It is governed more by other social pressures – like school and work.

But people who work with natural processes are keenly aware of the length of daylight: farmers, doctors and those who work with wildlife. Our biology and biochemistry cycles influence the effectiveness of our medications – a field called Chronobiology. Animals react to the length of day in a more intuitive way so ecologists must adjust the schedule of their studies as plants and animals prepare in advance to the approaching seasons as informed by the length of night.

We can change our schedules by switching on a light, but our biology can’t be fooled and if we ignore the natural length of day we will upset our natural (circadian) rhythms on which our health, and that of the ecosystem all depend.

One of Canada’s foremost writers and educators on astronomical topics, the Almanac has benefited from Robert’s expertise since its inception. Robert is passionate about reducing light pollution and promoting science literacy. He has been an astronomy instructor for our astronauts and he ensures that our section on sunrise and sunset, stargazing, and celestial events is so detailed and extensive it is almost like its own almanac.