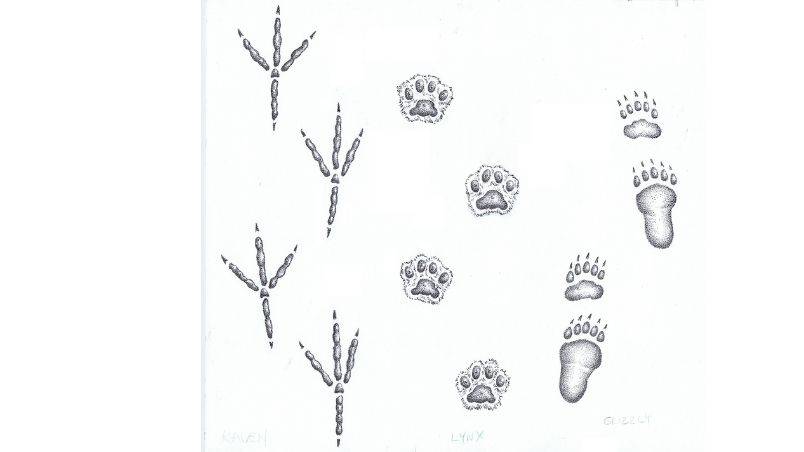

After a fresh fallen snow, it’s a delight to see tracks indicating our furry and feathered friends have been passing through. Not sure what you’re looking at? Our friends at the Hinterland Who’s Who program at the Canadian Wildlife Federation fill us in on who we might be tracking, and what they’re up to.

Grizzly Bear

A Grizzly bear is a solitary animal, who digs its den on a slope where snow adds insulation. The Grizzly bear typically “hibernates” for five to seven months, starting in late autumn through to March, though females emerge in April or May. Contrary to popular belief, Grizzlies are not true hibernators—in winter, their body temperature drops only a few degrees and their respiration rate is only slightly below normal. They also don’t fall into a deep winter sleep; at most they are lethargic and can even become active and roam not far from their den. In fact, cubs are even born during the winter months. It’s easy to mistake Grizzly tracks for Black Bear tracks and vice versa. On Grizzly tracks, claw marks will be longer, with toes closer together and less curved. If you find grizzly tracks, leave the area immediately. Planning an excursion to an area known for bear sightings? Be informed on proper bear protocol so you know what to do if you come across one. [For more info, you can visit: https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/mtn/ours-bears/securite-safety/ours-humains-bears-people]

Coyote

Coyotes are most likely monogamous, and mate in February or March. Active throughout the year, coyotes form pairs or small packs to hunt more effectively, especially in the winter. Although primarily a flesh-eater, the coyote will eat just about anything available—rabbits and hares are typical dietary staples, as are small rodents and larger animals like deer. Coyotes can be easier to spot in winter because of the lack of vegetation. Although similar to dog prints, you can identify coyote tracks because they are more oblong, the claws are less prominent and they are more compact. If the footprint is round, you may be tracking something else, like a bobcat. If you spot a coyote, remember that they are wild animals and should be respected; do not try to feed or pet them.

Grey Squirrel

Eastern grey squirrels breed in January and February and in June and July. They do not hibernate and in winter are most active around midday, perhaps to take advantage of the warmer temperatures. Their fur (grey or black) is thicker and longer in winter, and they rely on their fat reserves to survive the long, cold winters. You’ll know they’re around if you see gnawed husks and shells of nuts littering the ground. In winter small holes in the snow or in the ground indicate where squirrels have been digging to find hidden stores of nuts buried earlier in the year. They also often take advantage of bird feeders as a food source in the winter. When the squirrel bounds across the ground, the tracks are paired, hind prints slightly ahead of the fore prints. In the snow these tracks often look like two exclamation marks (!!).

Canada Lynx

Breeding for the Canada lynx takes place in February and March. Hares make up more than 75 percent of the lynx’s diet. The Canada lynx has large feet that are covered in winter by a dense growth of hair. It can also spread its toes in the snow, expanding its feet even further, so that they act like showshoes, which helps the lynx travel over snow. Like the cougar and the bobcat—two other members of the cat family native to Canada—the Canada lynx tends to be secretive and most active at night; it is rarely seen in the wild. Lynx tracks have a round shape with three lobes on the pad, and rarely show claw marks.

Common Raven

Interestingly, the common raven makes a wide variety of sounds and calls, even imitating other animals. The raven hunts in pairs, and a couple defends their territory year-round. Pairs mate for life, and egg-laying starts in February. Active year-round, the common raven does not migrate. In the winter, it feeds on carrion and other sources of meat.

White-tailed Deer

Most of the breeding for white-tailed deer occurs during the last three weeks of November, and males shed their antlers in January. They are active in winter, but are more susceptible to predators—deep snow makes it difficult for them to move freely, so they tend to follow trails and concentrate in “deer yards” (areas that provide food and shelter from storms and snow). In winter, they rely on green forage, such as winter-green forbs, grasses and sedges. Sometimes the move from summer to winter requires travelling many kilometres. White-tailed deer tracks are identified by their two toes (hooves), which form an upside-down heart-shaped track.

An editor with 15-plus years in the publishing business, Catalina Margulis’ byline spans travel, food, decor, parenting, fashion, beauty, health and business. When she’s not chasing after her three young children, she can be found painting her home, taming her garden and baking muffins.